Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan: Heading Toward Confrontation

Dr. Zmkan A. Saleem

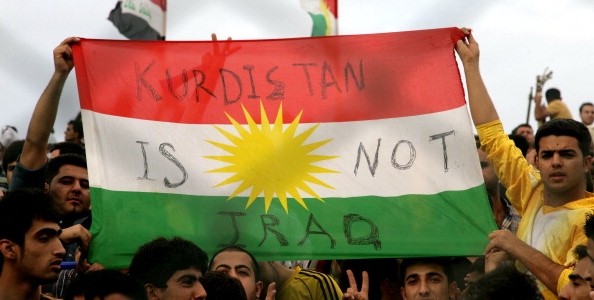

The Islamic Republic of Iran and the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq maintain cordial relations, and the two neighbors have publicly cooperated in battling the Islamic State (IS). However, this might change soon. The authorities in Tehran are increasingly frustrated with the Kurdish leadership’s decision to hold an independence referendum on September 25 in territories under control of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Tehran speculates that the vote would speed up Kurdistan’s walk toward full independence, an event which Iran sees as a challenge not only to Iranian stability but also to their regional ambitions.

The KRG’s announcement of the referendum date drew direct responses from a number of top Iranian officials, including from the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Khamenei voiced his opposition to the referendum and reiterated Iran’s commitment to Iraq’s territorial integrity during a meeting with Iraqi prime minister Haider al-Abadi in Tehran.

But why does Iran so vehemently deny the right to independence to Iraqi Kurds?

Iran is home to a sizable Kurdish minority of its own. The Islamic Republic ties its own survival and territorial integrity to the continued dominance of the country’s Shiite majority. As a result, the ruling elite in Tehran perceives any ethnically-framed demand as a challenge to its authority and internal cohesion.

Consequently, Tehran has either ignored or harshly responded to Iranian Kurds’ demands for socio-cultural and political rights. Iranian Kurds – the majority of whom are Sunni – have suffered economic hardship and political exclusion under the Shia regime.

Iran fears that the establishment of an independent Kurdish state in Iraq would inspire separatism in Iranian Kurdistan, or at least bolster the disaffected Iranian Kurds to seek autonomy and make demands of Tehran for greater rights. From Tehran’s perspective, this could in turn destabilize the Islamic regime’s authority in Iranian Kurdistan and ultimately damage the country as a whole.

Iran is also worried that Kurdish designs to break away from Iraq could alter the regional balance of power against its strategic interests. Tehran thinks that Kurdish independence would lead to the final disintegration of Iraq along ethno-sectarian lines: a central Sunni-Arab state, a Kurdish state in the north, and a Shiite-Arab state in the south.

Tehran considers a Sunni-Arab state in the middle of Iraq a strategic disaster, as it would likely be dominated by Saudi Arabia. This could eventuality jeopardize the land corridor that Tehran has created over the past four years that connects Iran to its regional allies in Syria and Lebanon via Iraqi territories.

A Kurdish state in northern Iraq would be a win for Turkey, the United States, and Israel, all regional and international rivals of Tehran.

Compared to Iran, Turkey has gained much greater leverage over Iraqi Kurdistan through the strong alliance that Ankara has formed with Masoud Barzani, president of Iraqi Kurdistan and leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which controls most of the levers of power in the KRG. Iran, meanwhile, has relied largely on its connections to the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), whose power in the Kurdish region has declined due to factional disputes and rivalries within the party.

Part of the frustration for Iran is that it has been watching Barzani build domestic consensus for holding the referendum primarily by persuading a powerful faction within the PUK to jump on the bandwagon and join the march toward Kurdish independence.

Anxious about such an eventuality, Iran recently invited a delegation from the PUK to Tehran, perhaps to test the Kurdish party’s commitment to backing the referendum. Received by Ali Shamkhani, secretary of Iran’s National Security Council, in Tehran on July 19, the PUK delegation made it explicit that their party would support the planned vote on Kurdistan’s independence from Iraq.

It appears that Iran has miscalculated the PUK’s domestic political maneuvers and interests. After all, the PUK is a secular-nationalist Kurdish political party with a strong dedication to Iraqi Kurds’ right to self-determination and statehood; it is not beholden to Iran in the same way Hezbollah is, for example. Neither the PUK nor its splinter, the Gorran party – the KDP’s staunch opponent – have ever really been against Kurdish independence from Iraq.

The PUK wants to ensure that it will not be marginalized in governing an emerging Kurdish state, while the Gorran Party claims that its aim is to make it hard for the KDP to turn the independent Kurdistan into a future Barzanistan, a sovereign Kurdish entity ruled exclusively by Barzani and his family.

Both parties, the PUK and Gorran, have been waiting for the KDP to make greater political concessions before they give in entirely to Barzani’s demands and mobilize their constituencies behind the referendum in September. Iran has little power over this domestic political dynamic.

As Tehran sees it, Washington’s diplomatic ties and military cooperation with the Iraqi Kurds would allow the United States to utilize an independent Kurdish state as a launch pad for regime change in Tehran, or at least for weakening Iran’s regional position. The Iranian regime’s hardliners tend to foresee an alliance between an independent Kurdistan and Israel against the Islamic Republic.

There is some chance that Tehran will choose coercive methods that could include encouraging Iraqi Shia militias against Kurdish Peshmerga forces. But a Shiite-Kurdish fight in Iraq, ignited by the Islamic Republic, would inevitably extend to Iran. Any Iranian attack on the Iraqi Kurds, whether by Iranian or Iranian-directed forces, would unleash a wave of resentment among the Kurds, including the Iranian Kurdish population, against the Islamic Republic. Thus, the very means that Iran could employ to stop the Iraqi Kurds from breaking away from Iraq would generate the same conditions that Iran fears an independent Kurdish state would create.

The United States should not allow Iran to subvert the Iraqi Kurds’ quest for independence, as they have been an important ally to Washington in Iraq. If the Iranian regime gets its way, it will only be emboldened to act in the same manner against the United States’ other allies in the region.

The United States has invested great military efforts and resources to defeating the Islamic State in Iraq and bringing a degree of stability to the country. An Arab-Kurdish war sponsored by Iran over Iraqi Kurdistan’s independence will only pave the way for chaos, instability, and extremism to reemerge in Iraq, which will again result in wasting American money and lives.

The United States should therefore should commit greater diplomatic efforts in initiating a serious dialogue between Baghdad and the Kurdish leadership in order to find compromise. If Washington comes to the conclusion that regional stability is best served by separating Kurdistan from Iraq, then the United States should encourage Iraqi authorities to peacefully and diplomatically come to terms with Kurdistan’s independence.

However, Washington should also be aware that Iraqi Kurds are fed up with the United States using them politically to counterbalance any effort by Iraqi Shia – Iran’s allies – to impose control over Iraq. At the same time, Barzani and his fellow Kurdish leaders should listen to the United States and be very wary of acting against such a strong ally’s advice and interests. A strong, inclusive, and economically sustainable independent Kurdistan is only possible if it is both recognized and supported by the United States.

It is true that some of the Kurdish leaders have shown authoritarian tendencies and that the Kurdish region of Iraq faces an array of socio-economic challenges. But there is a genuine desire among large parts of the Iraqi Kurdish population – particularly the Kurdish youth – for democracy, transparency, rule of law, and religious tolerance. These are the very values that the United States aims to uphold globally, and ones that Iran does not.

English

English العربية

العربية